Education

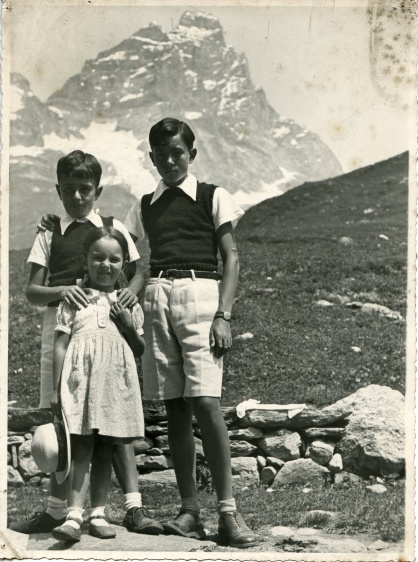

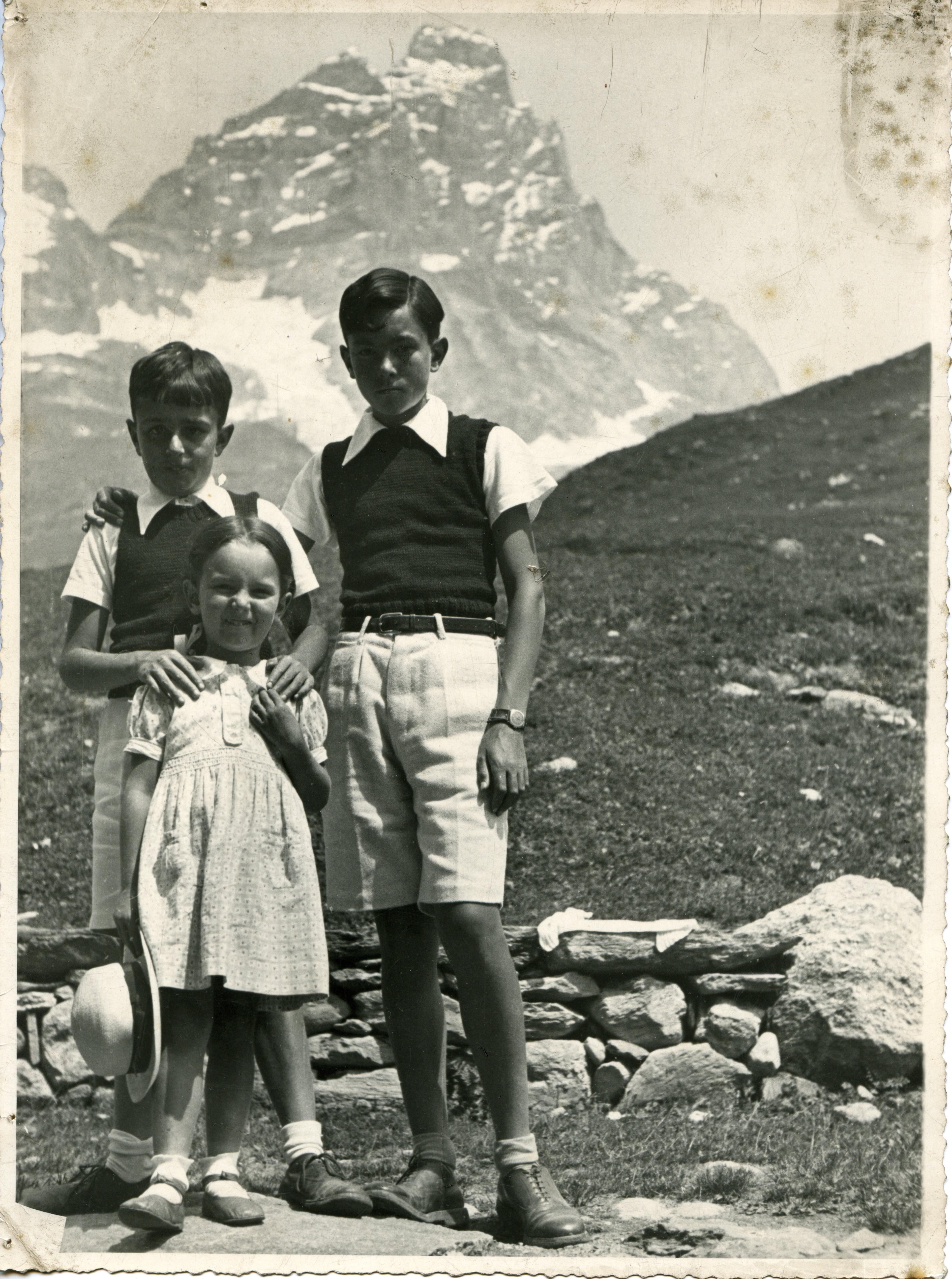

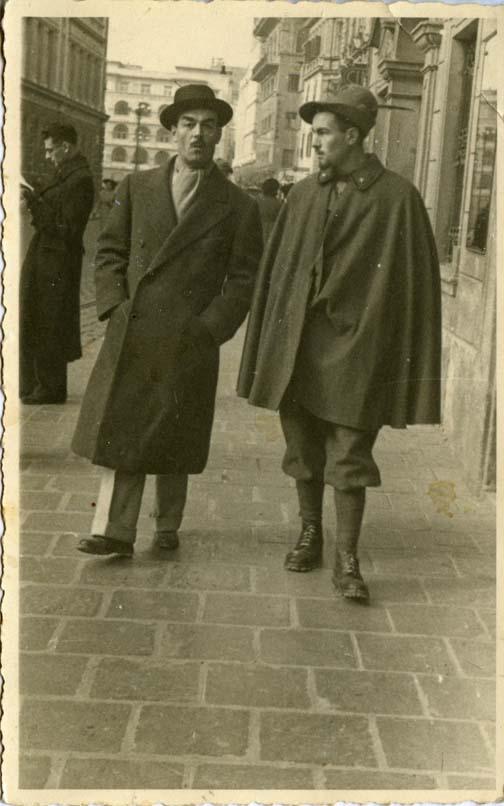

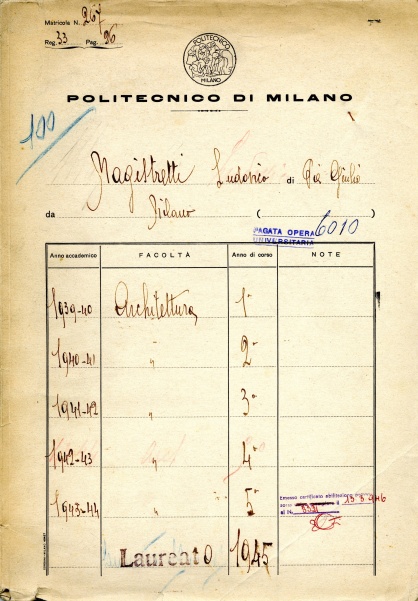

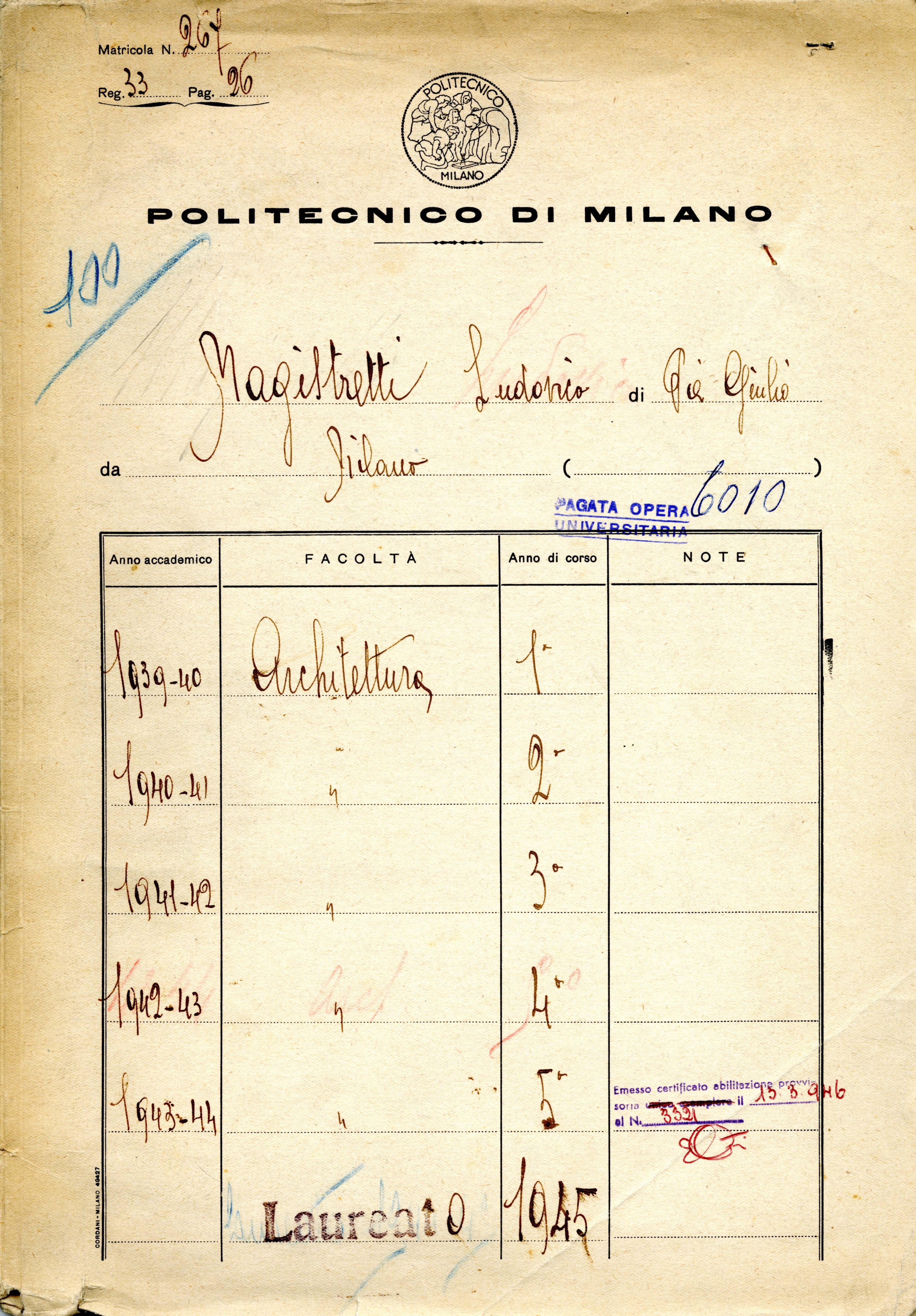

Ludovico Magistretti was born in Milan on 6th October 1920. He came from a family of generations of architects: his great-grandfather Gaetano Besia built the Palazzo Archinto, then Reale Collegio delle Fanciulle Nobili, in Milan; his father, Pier Giulio Magistretti, was involved in the design of the Arengario in Piazza del Duomo. Vico, as he was called by family and friends, went to Parini High School and in autumn 1939 enrolled in the Faculty of Architecture at the Royal Polytechnic in Milan.

"I was born in a middle-class bourgeois family. My grandfather was a high-school teacher and my father worked as an architect. (…) So I was born in a very Milanese milieu, indeed our Milanese origins go back several generations. On the other hand my great-great-grandfather, coming from my mother's side of the family, was the architect Gaetano Besia, who designed the really beautiful Collegio Reale delle Fanciulle, also known as Palazzo Archinto, that stands on the corner."

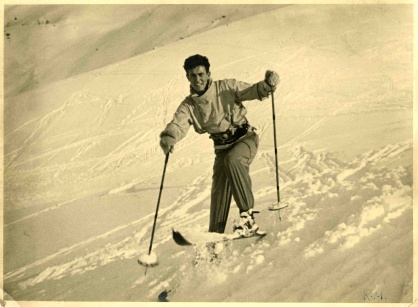

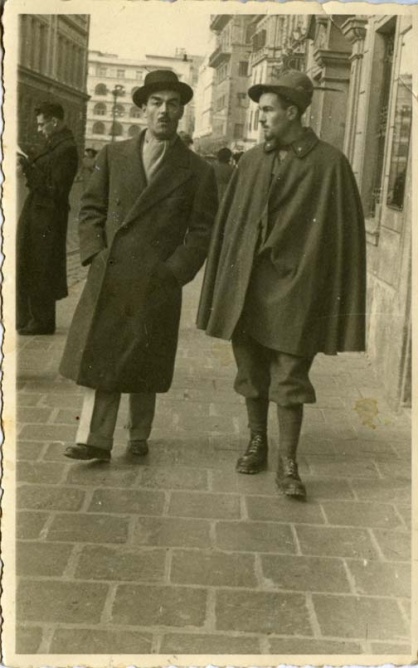

After 8th September 1943, during his military service, he left Italy and escaped to Switzerland to avoid being deported to Germany. There he took some academic courses at the Champ Universitaire Italien in Lausanne, set up at the local university.

During his stay in the Swiss city he met Ernesto Nathan Rogers, the founder of the BBPR firm who had taken refuge in Switzerland after racist laws were passed in Italy. This was a key encounter in Magistretti’s intellectual and professional development, since the architect from Trieste turned out to be his maestro.

"I will always be eternally grateful for everything about architecture I learnt from my teacher Ernesto Rogers. Ernesto Rogers was one of my dearest friends, a true friend because he was somebody who always managed to distinguish what is important from what is less so when studying projects, when looking at what we were doing, what we were designing, making a very clear distinction between what counted and what did not."

He returned to Milan in 1945, where he graduated in Architecture from the Polytechnic on 2nd August. He then immediately began his career at the firm owned and run by his father, Pier Giulio, who died prematurely that same year.

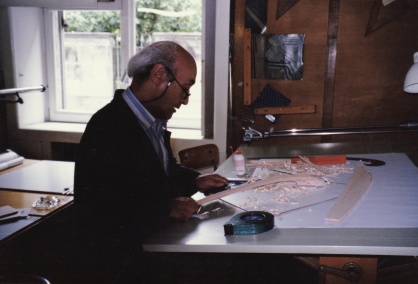

Here, in his father’s small firm, he spent his entire career with Franco Montella, his extraordinary assistant from 1951 till 2003.

"Because of my father, I’ve got into the habit of going to the studio since I was a little boy. Therefore I got used to the smell of the studio."

In 1946 he participated in the RIMA exhibition (Italian Assembly for Furniture Exhibitions), held at the Palazzo dell’Arte, designing some small almost self-made pieces of furniture and then, in 1947 and 1948, he took part together with Castiglioni, Zanuso, Gardella, Albini and others in the exhibitions organised by Fede Cheti, a furniture fabric maker, held at her own workshop.

“The 1948 Fede Cheti exhibition was, I believe, the true birth of ltalian design even before the Triennale exhibitions.”

During the VIII Triennale, he was involved with Mario Tedeschi in the joint project for the QT8 neighbourhood, designing houses for veterans from the African campaign and also Santa Maria Nascente church.

The 1950s

During reconstruction operations in Milan from 1949-59, Magistretti designed and constructed about 14 projects for INA-Casa in conjunction with other architects.

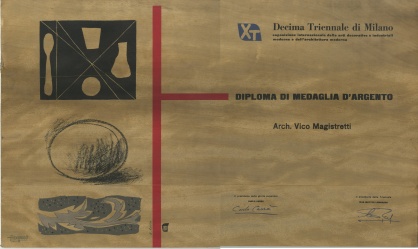

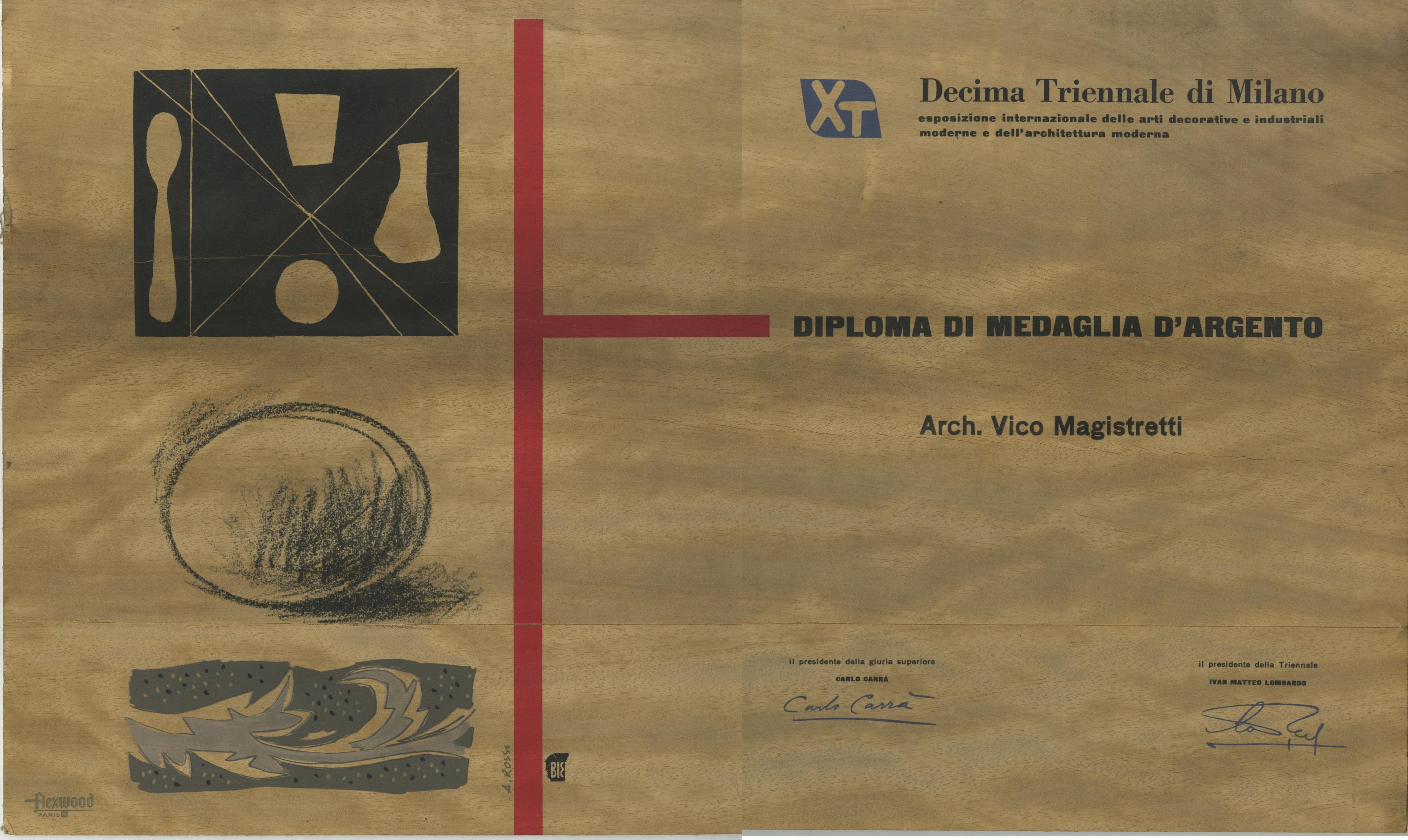

He notably took part in the IX (Gold Medal) and X (Grand Prix) editions of the various Triennials in Milan.

“The Milan Triennale in the early years after 1945 was a powerful tool for broadcasting information, spreading ideas, providing scope for the most extraordinary experimentation. This institution is what led us to find out what was going on outside Italy, and not just in the field of architecture, I might add.”

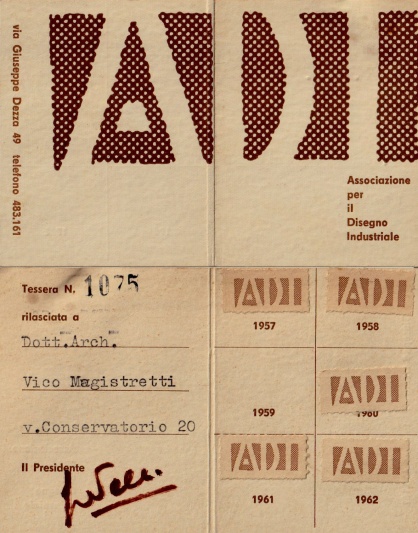

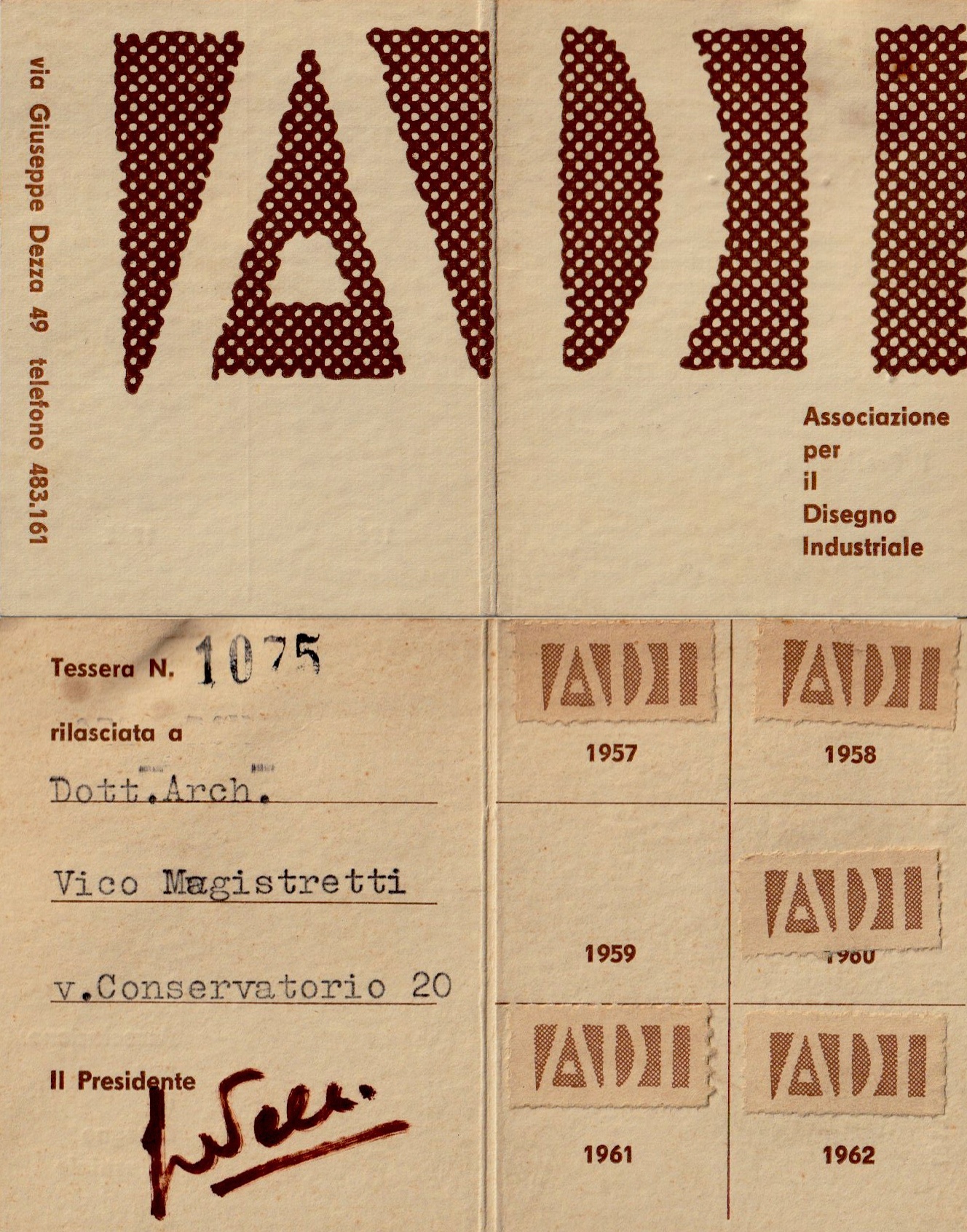

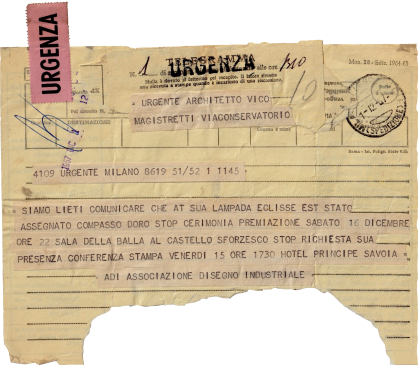

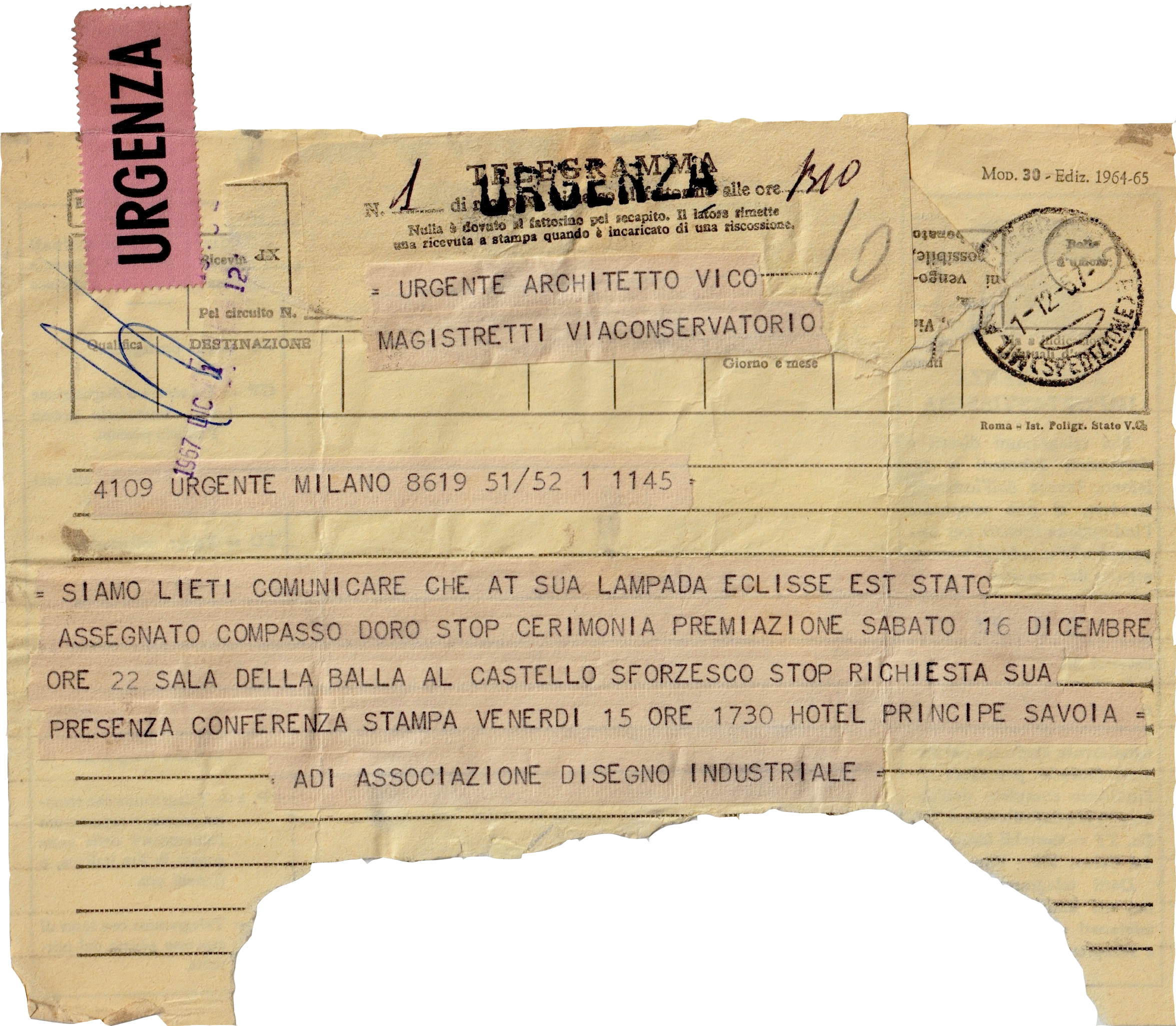

In 1956 he was one of the promoters of the ADI, Association for Industrial Design, together with De Carli, Dorfles, Gardella, Munari, Nizzoli, Peressutti, Rosselli, Steiner and two companies (Kartell and Officine Meccaniche Pellizzari).

In the same year he was part of the Compasso d'Oro Award jury for the first time, followed by many others.

The young architect was involved in plenty of activities and came up with lots of new ideas and proposals in the 1950s, which, in a short space of time, saw him rise to the status of one of the most brilliant exponents of the “third generation”, partly thanks to the construction of two key buildings in Milan: the Tower building in Parco Sempione in Via Revere (1953-56, in conjunction with Franco Longoni) and the office building in Corso Europa (1955-1957).

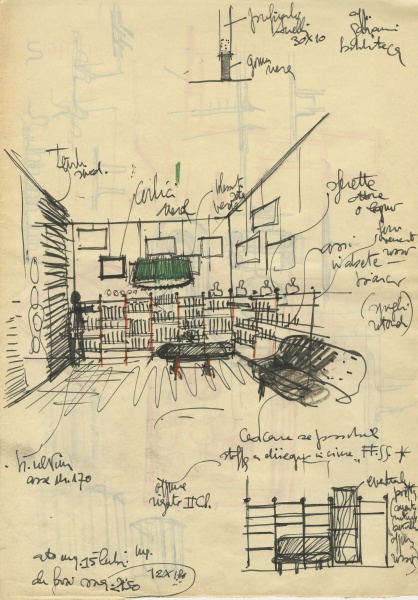

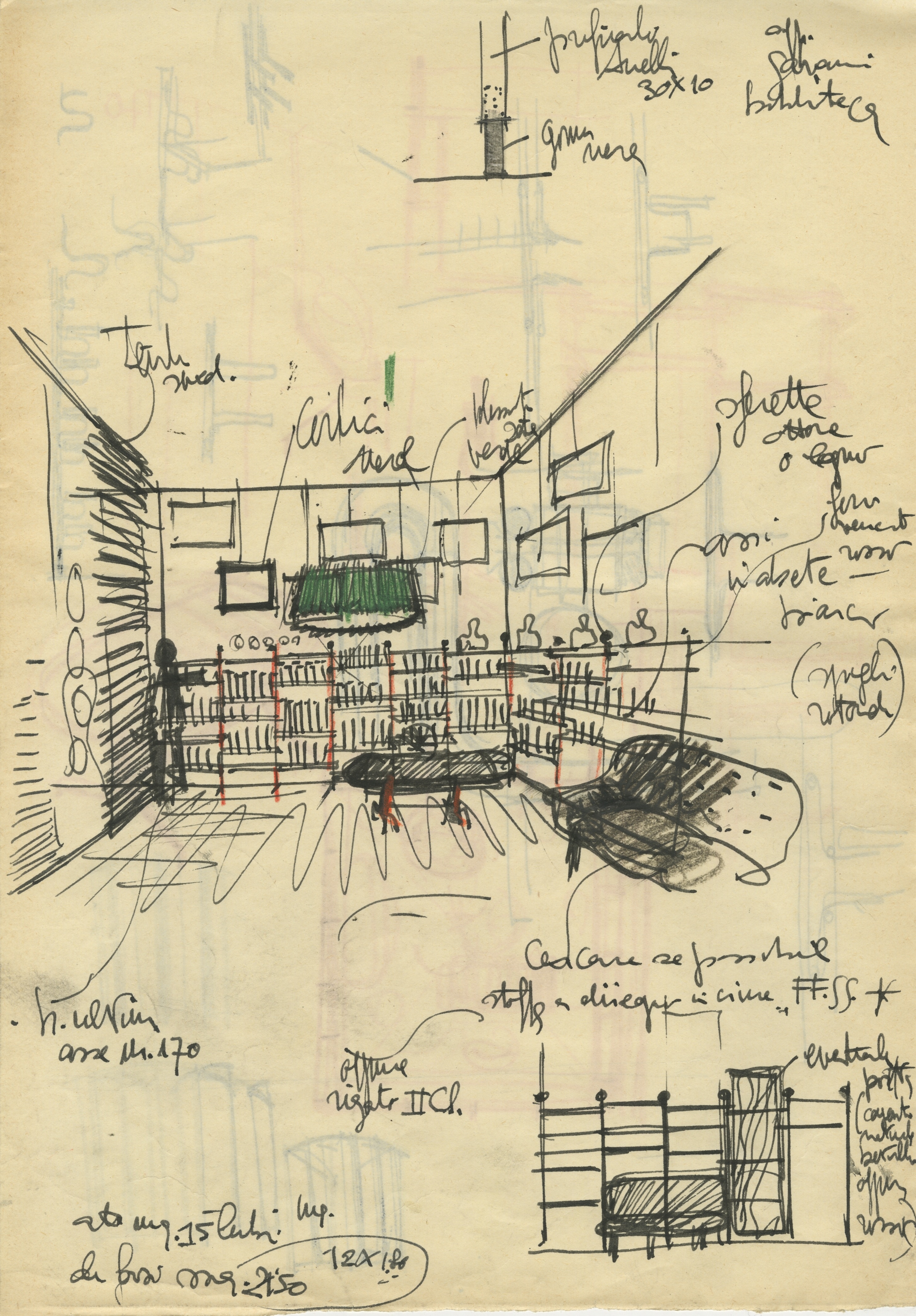

In these years, but also in the following decades, Magistretti designed many home interiors: from large flats to residential cells in residential buildings. These projects were free from any pretentions in terms of decoration and confined to creating structures suitable for their inhabitants, they shed light on that typical taste of Magistretti for an idea of elegantly free, nonchalant living, reflected in his apartments and in his design, becoming a characteristic linguistic trait. These included: the flat in Via Goito in Milan (1953-59) and the one in via Verri (1953-54) in the 1950s; the living cells of the house in Corso di Porta Romana in Milan (1962-67) and of the MBM houses in Gallaratese in Milan (1963-71) in the 1960s.

“A house should be simple, qualified by its spaces. And it should be generous, i.e. it should welcome anything, because the furnishings, the image of the house, are a pitiless self-portrait of the people who live there. A person is always narrated by his house. This is why I refuse to suggest, “put a green sofa instead of a yellow one.” I make a structure that gives the house character, not as a matter of fashion but as a matter of spaces. Then even if you fill them up with junk, it’s not important. What is important is that the structure of the house should stand up.”

In 1959 he took part in the CIAM Congress (International Modern Architecture Congress) held in Otterlo in the Netherlands, during which the Italians presented Velasca Tower designed by the BBPR, the Olivetti canteen designed by Ignazio Gardella, the Arosio house in Arenzano designed by Vico Magistretti (1956-59), and the houses in Matera designed by Giancarlo De Carlo. These works caused a real scandal and were, in some respects, emblematic of the deep crisis which struck the CIAM over those years, until then the undisputed protagonist of architectural debate, so much so that the 1959 Congress turned out to be the last.

Magistretti’s project for a small house in Arenzano allowed him to discover his own language and own image.

“Together with Ernesto N. Rogers, Ignazio Gardella and Giancarlo De Carlo I attended the last congress of the C.I.A.M. in Otterlo-Holland where the Sacred College, in this case of the C.I.A.M., excommunicated us because we had dared to use architectural elements typical of the local landscape in the projects we presented. In my case, very modestly, shutters on windows.”

The 1960s

His work as an architect was almost totally focused on the issue of housing and living from the 1960s onwards, as he developed his own extremely expressive idiom, which, even though it was heavily criticised at times, made a real impression on the architectural scene in Lombardy during that period, making him one of its leading figures.

Magistretti was one of the founding fathers of so-called Italian Design, a phenomenon which he himself described as “miraculous” and which only happened thanks to the coming together of three key players: architects, manufacturers and artisans.

He began working with some exceptional manufacturers from the end of the 1960s, including Artemide, Cassina and Gavina, designing objects for them which are still “classics” of modern-day production.

"The birth of Italian Design owes a lot to the close dialogue between production and those who design: it was born from manufacturers who wanted to change, grow and evolve. And - also for this reason - it has lasted since 1960."

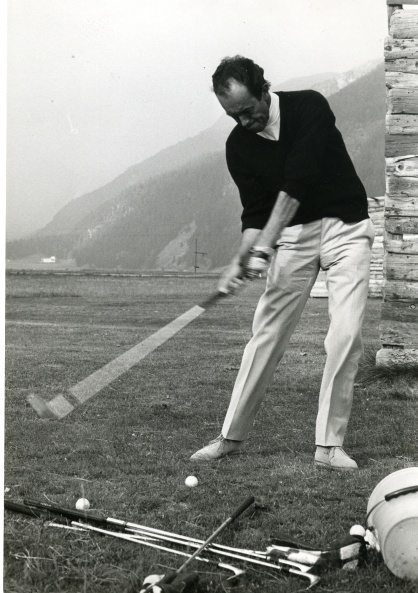

The first product designed by Magistretti dates back to 1960: the Carimate chair, designed to furnish the restaurant of the golf club he designed in the same year with Guido Veneziani in Carimate. The chair was then brought into production by Cassina.

“I had designed a chair, for a work of architecture: the red chair that we were talking about at the beginning - the one I did in 1959-60 that was discovered at the Triennale by Cesare Cassina. Its name is Carimate. It was my first industrially manufactured product and one of the most widely sold. Its forms were reminiscent of a children’s game. And it all started with the 1960 Triennale, where a group of other objects were exhibited that I still find extraordinary even now.”

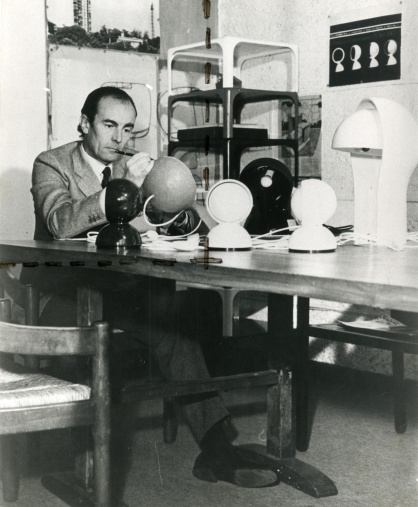

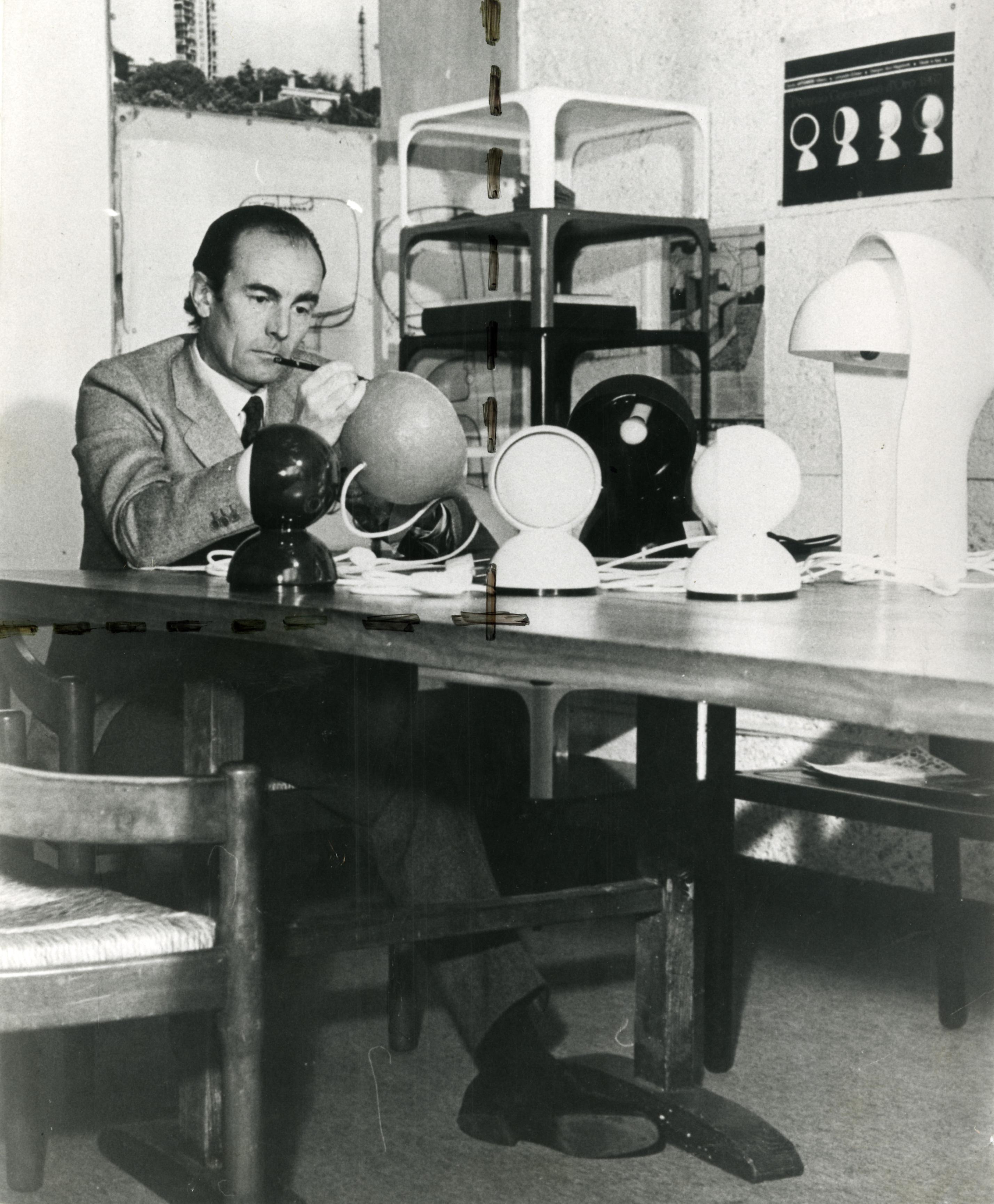

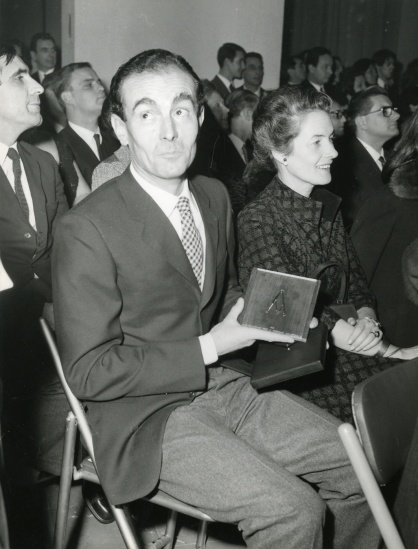

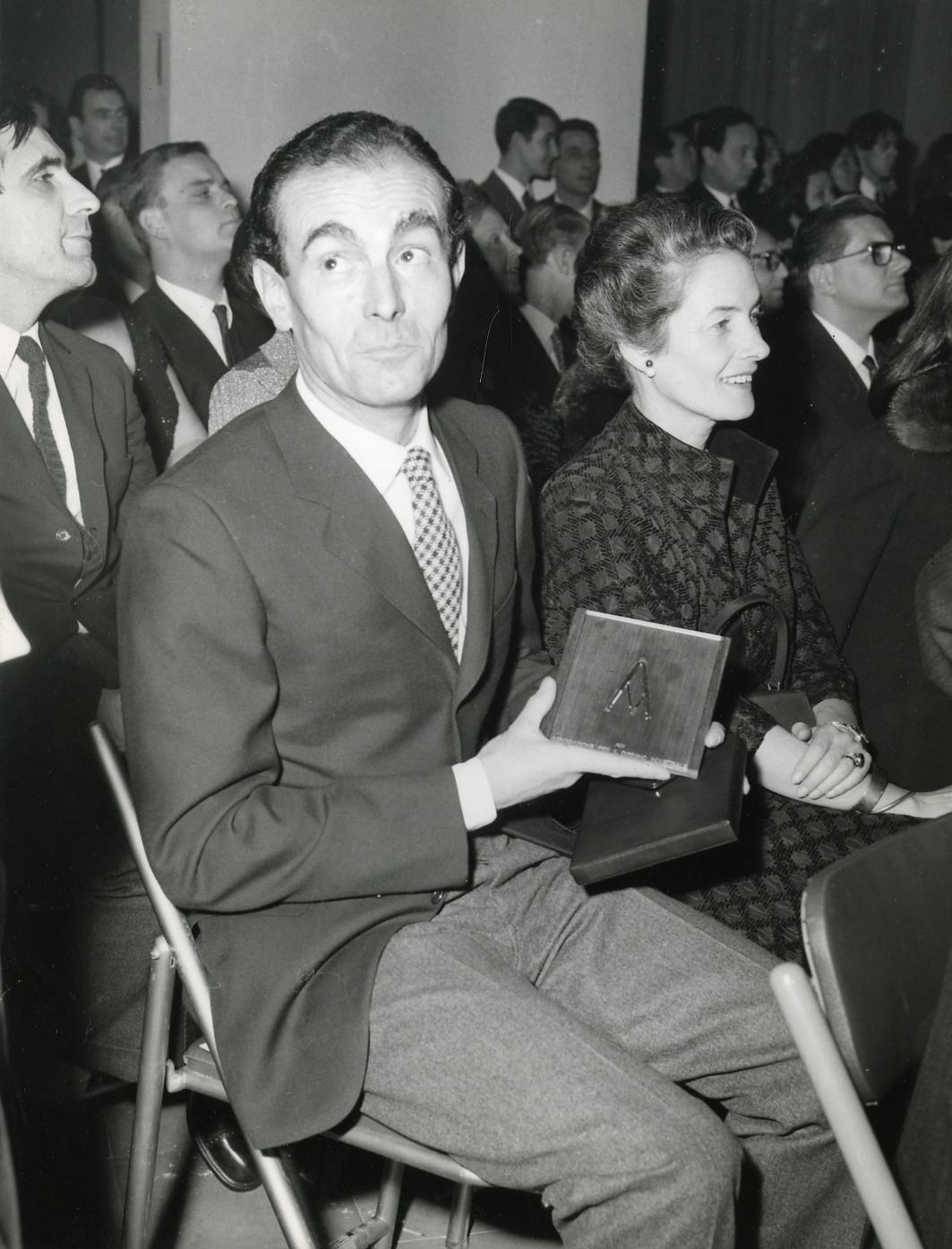

He also designed a set of lamps for Artemide, including Mania (1963), Dalù (1966), Chimera (1969), the extremely famous Eclisse (1967, Compasso d’Oro award 1967).

After the Demetrio coffee tables (1966), other pieces of furniture designed by Magistretti include Selene chair (1969), which, with the Panton Chair and Joe Colombo’s Universale, vied to become the world’s first plastic chair.

“But the simplicity of an umbrella, the nothingness and inherent tension in an umbrella, make it the object I would most like to have designed. But I ended up designing that stupid lamp over there (editors’ note: Eclisse), which is, however, still around because it left its mark (even on burnt fingertips from twisting the lamp) on a few generations. That is a good feeling.”

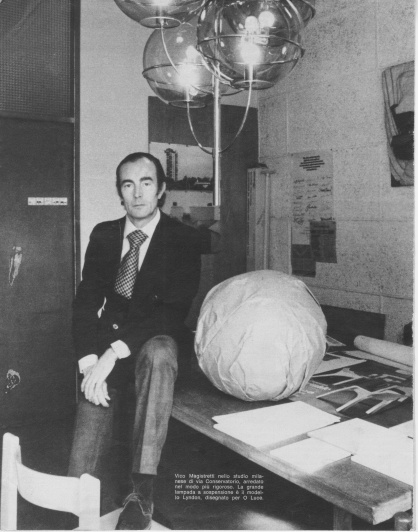

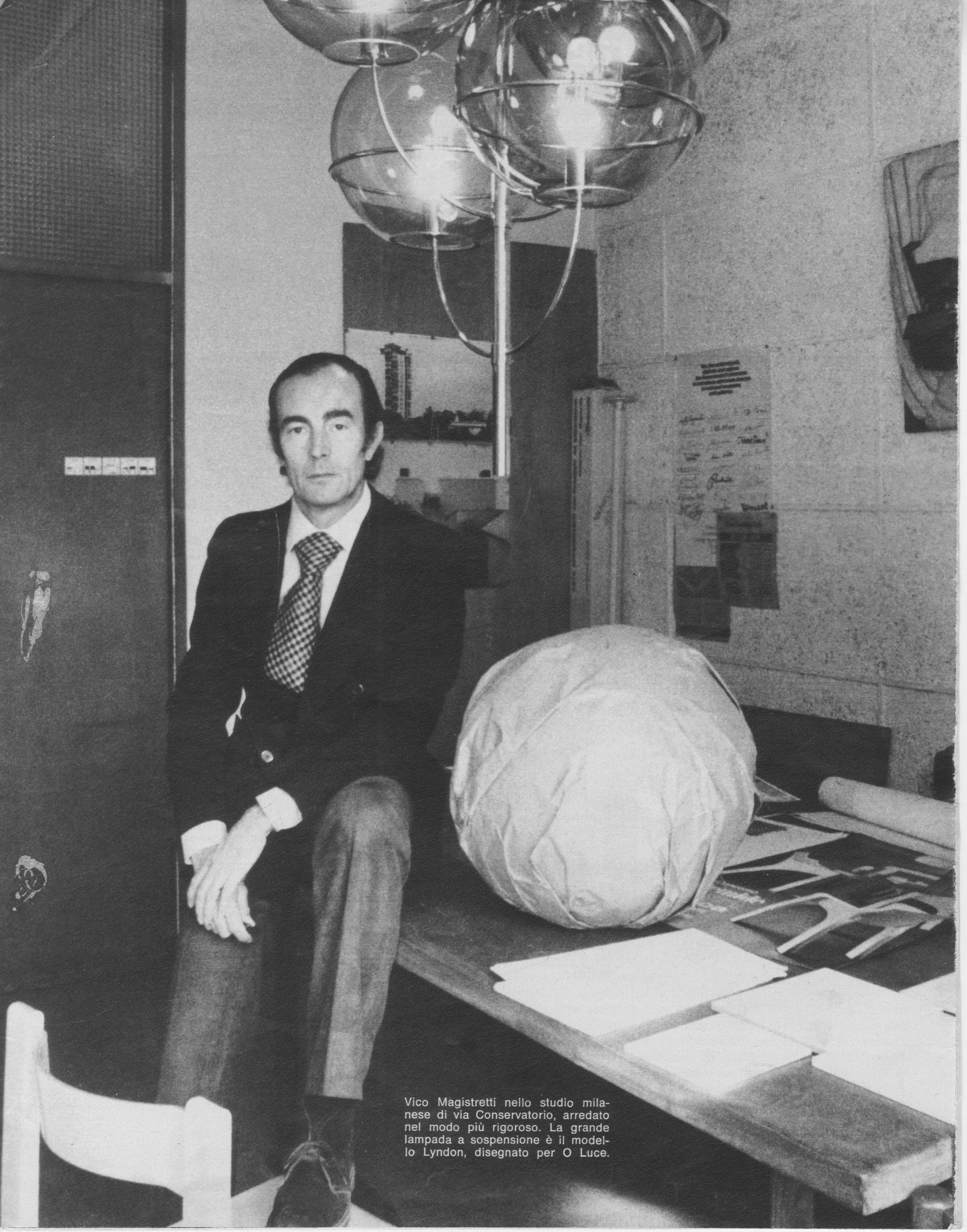

As regards architecture, this was the period when he built: the house in Piazzale Aquileia in Milan (1961-64), the Bassetti house in Azzate (1959-62), the Cassina house in Carimate (1964-65), the building in Via Conservatorio in Milan (1963-66), Cusano Milanino Town Hall (1966-69), the Milano San Felice neighbourhood in Segrate (1966-69, in partnership with Luigi Caccia Dominioni).

The 1970s

The next decade saw Magistretti’s architectural enterprises increasingly backed up by his work as a designer.

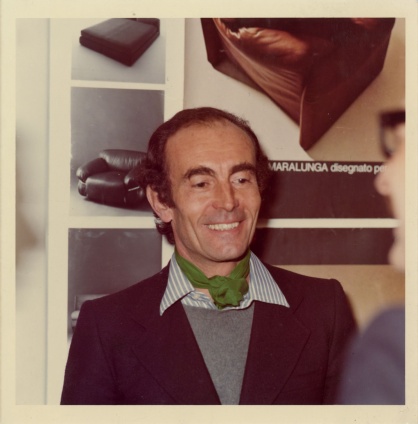

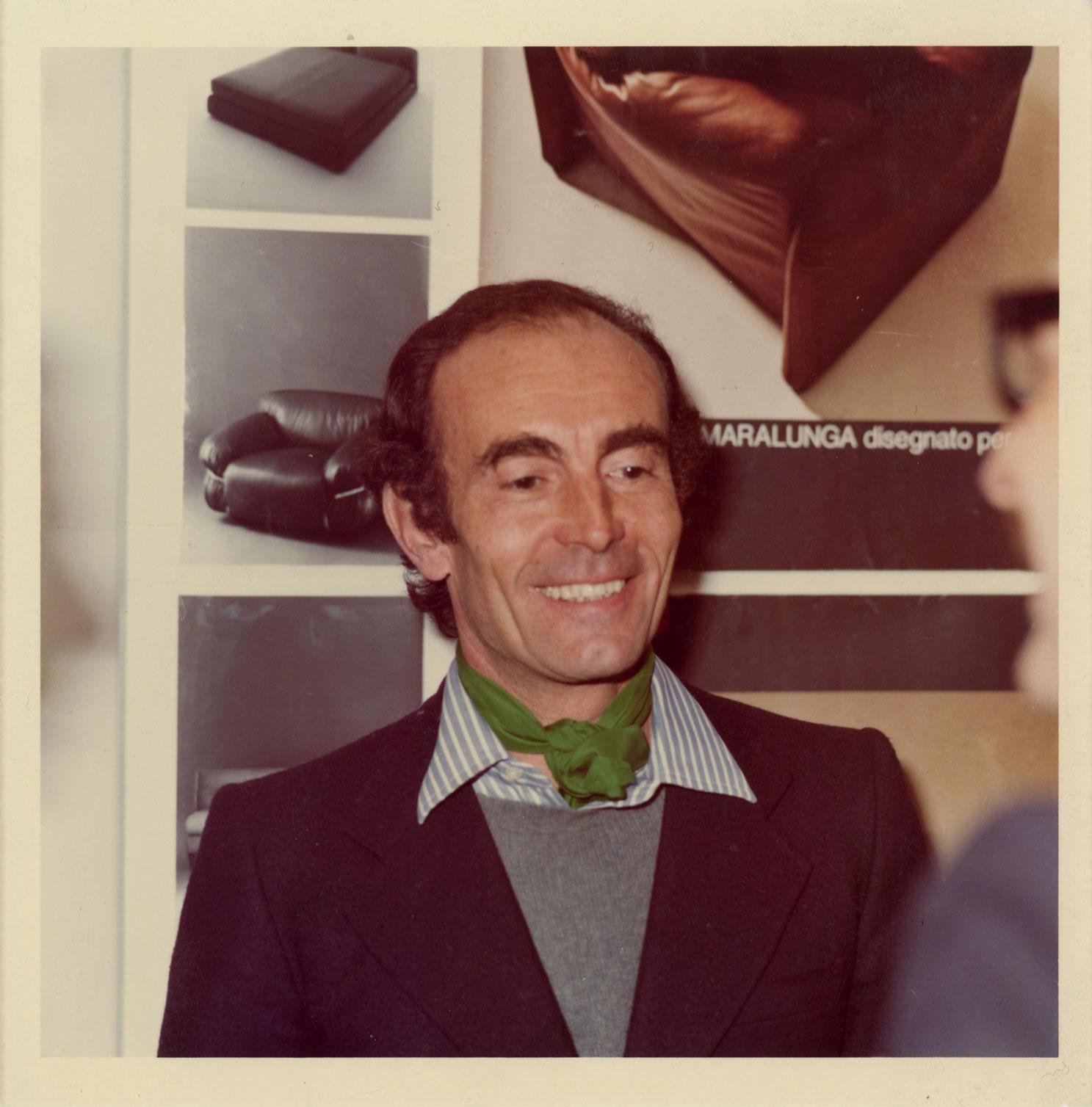

After the Carimate chair he went on over subsequent years to design numerous other objects for Cassina, notably including the Maralunga sofa (1973, Compasso d’Oro award in 1979), the Sindbad sofa (1981) and the Veranda armchair (1983).

From 1973 to 1979 Magistretti was also the art director and main designer for Oluce, giving the company’s production range its own unmistakable style. His masterpieces, icons recognised all over the world, include: Snow (1974), Sonora (1976), Atollo (1977, Compasso d’Oro award 1979), Pascal (1979) and Kuta (1980).

"In a lamp the most important thing is the light. I thought I'd show three different lights depending on the parts of the lamp. A dark dome (it hides the light bulb), a very bright and white cone. A gray base cylinder. It fit on a table. Much produced."

At the end of the 1970s, Vico designed the Nathalie bed for Flou (1978), the first fully upholstered textile bed and the first of many projects designed by Magistretti for the company directed by Rosario Messina.

“The secret of Nathalie's success lies in a basic innovation, later much copied: the use of the duvet in a rigid form, which until then had always been used only as a blanket while with Nathalie it becomes a soft headboard to lean on.”

As regards architecture, this was the period when he built the house in Via San Marco in Milan (1969-71), the Muggia house in Barzana (1972-73), the restaurant Locanda dell’Angelo in Amelia (1973-75) and the Biology Department for Università Statale di Milano (1978-81, con F. Soro).

The 1980s

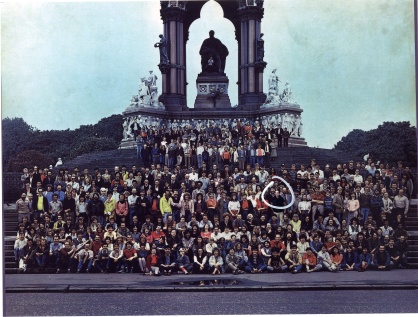

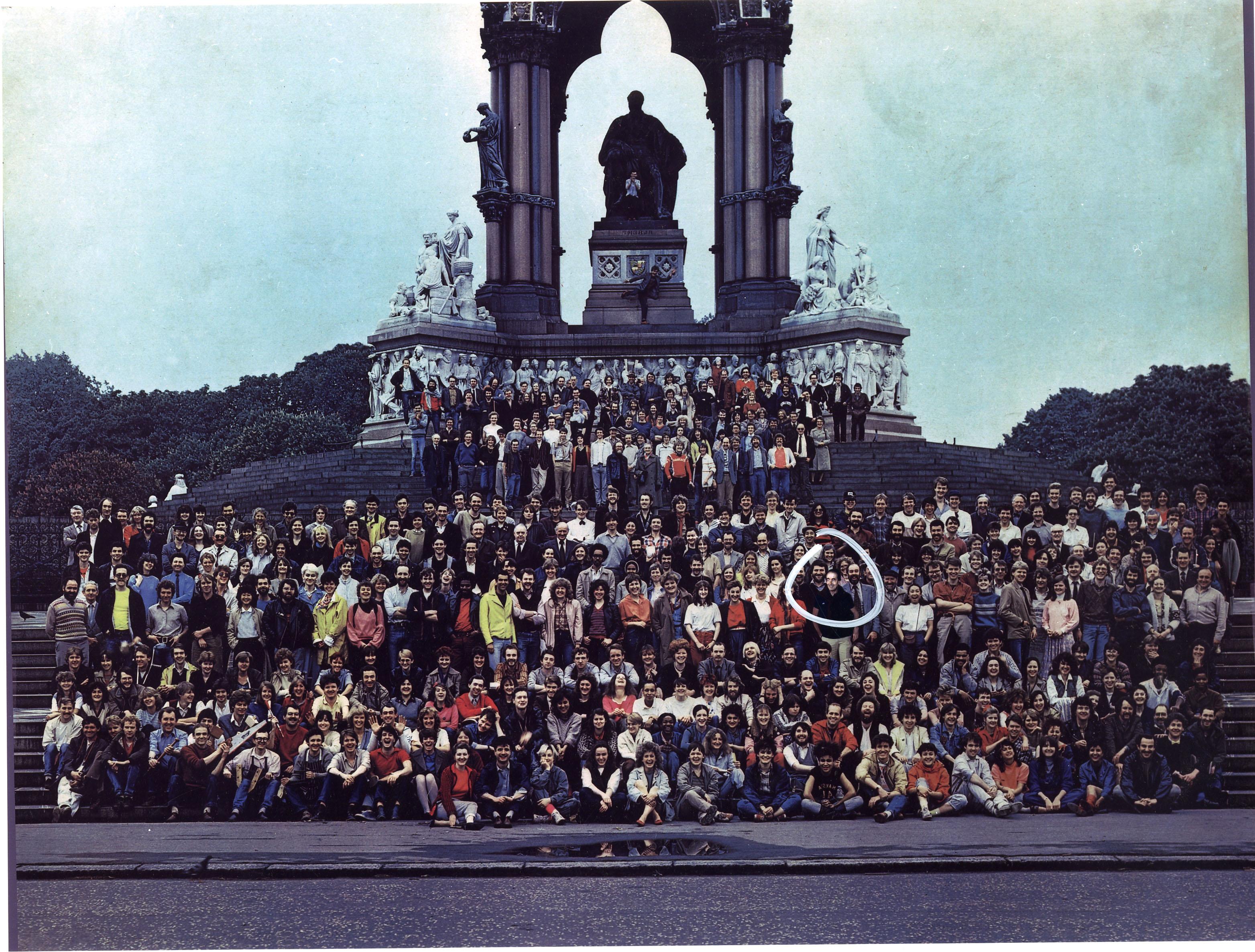

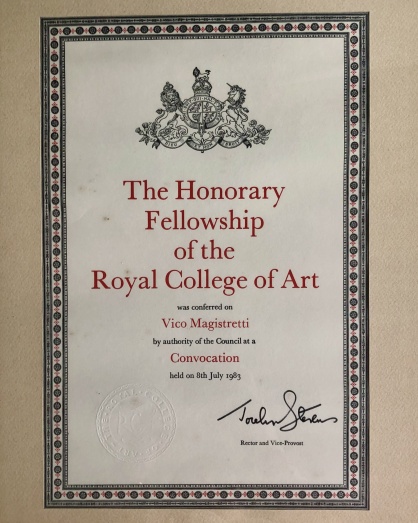

Magistretti’s teaching career began back in 1979 at the Royal College of Art in London as a visiting professor, where he was also made an honorary member in 1983.

“I love that country because it is a real, great nation that recognizes itself in the State, which governs based on consensus. I am therefore grateful to the Royal College of Art that allowed me to deepen my knowledge of England and English people.”

Vico Magistretti’s love of Great Britain was reciprocated and in 1986 he received a prestigious British prize: the gold medal awarded by SIAD, Society of Industrial Artists and Designers.

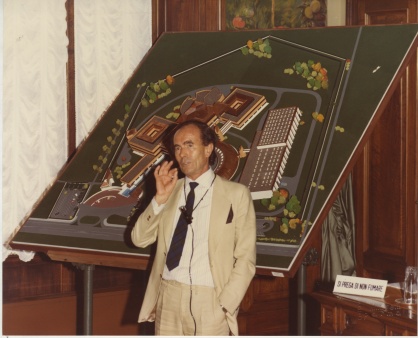

At the same time as he was teaching – since 1987 he was also professor at the Domus Academy in Milan – he continued working as an architect in Italy and abroad. His architectural works from that period include the Tanimoto house in Tokyo (1985-86), the Centro Servizi Cavagnari of the Cassa di Risparmio in Parma (1983-85) and the Tecnocentro of the Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna in Casalecchio di Reno (1986-88).

At the end of the 1980s he also began a partnership with a leading publisher: Maddalena De Padova. After giving up the ICF trademark – for ICF Magistretti designed several products such as Davis (1978) and INTERparete (1981) – in the late 1970s including the licence to manufacture Herman Miller products, Maddalena created a range of furniture and objects bearing the De Padova trademark, later named “è De Padova”, whose business partners included such great designers as Achille Castiglioni and Dieter Rams, but above all Vico Magistretti.

The “è De Padova” collection designed by Magistretti includes such classics as: the Marocca chair (1987), the Vidun table (1987), the Raffles sofa (1988) the Silver chair (1988) and the Incisa chair (1992).

"The seat and the back of my Silver chair for De Padova come from the baskets used for eggs in Japanese markets. Same material, same proportions, no fantasy."

The 1990s

The most important architectural projects carried out in the 90s are the Milanese Underground Railway depot in Famagosta (1989-2002), the new offices for the Barilla company in Pedrignano (1991-94) and the Esselunga supermarket in Pantigliate (1997-2001).

Whereas a lots of the architect’s design projects were brought into production.

Vico Magistretti’s work in this field became increasingly diverse in relation to the different companies with which he set up business partnerships, designing more than just one object for them.

For Flou he invented new types of beds including, after Nathalie bed, Tadao, whose base and headboard represent a simple reworking of a plank structure.

Similarly, in his partnership with Schiffini Mobili Cucine, Magistretti did not simply settle for conventional styles. His Campiglia kitchen unit (1990) resorts to less cantilever strictures through the introduction of cabinet-type furniture. Solaro (1995) transforms the conventional doors of its basic elements into handy spacious drawers. Cinqueterre (1999) uses a semi-manufactured industrial article, an extruded sheet of undulating aluminium, which gives shape to each individual feature.

In the 90s Magistretti began to work also with Kartell, Campeggi and Fritz Hansen. For the first one, Vico designed four chairs and one of these – Maui (1996), which is made one single piece of plastic – due to the international success it attained, is probably the best-selling chair designed by Magistretti.

"(..) when I design a chair for Kartell like the Maui (one of the most beautiful chair I designed, in 1996), and they sell one hundred and fifty thousand every year, it becomes clear that the great secret of design is the number: the large number."

Magistretti got the chance to apply a reworking of certain articles of traditional anonymous design when working with Claudio Campeggi, designing some rather unobtrusive objects bursting with his own personality: the Kenia chair (1995), a kind of new and light Tripolina or the Ospite bed (1996), which is a reinterpretation of a cot bed.

In the mid-90s Magistretti began to collaborate with the Danish company Fritz Hansen, designing three chairs: Vico (1994), VicoDuo (1997) and VicoSolo (1999).

“My greatest wish came true, I had always wanted to come to work for Fritz Hansen and stay in Denmark; it is a country I love and admire. My fascination for Denmark started when I as a young architect and learnt about Danish modernism and saw the furniture that was created by architects such as Arne Jacobsen, Finn Juhl, Hans J. Wegner, Barge Mogensen and Poul Kjaerholm. Danish furniture from the 50s has always been an inspiration to Italian architects.”

In 1994 Magistretti was awarded the Compasso d’Oro award for lifetime achievement.

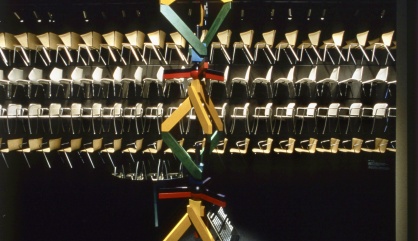

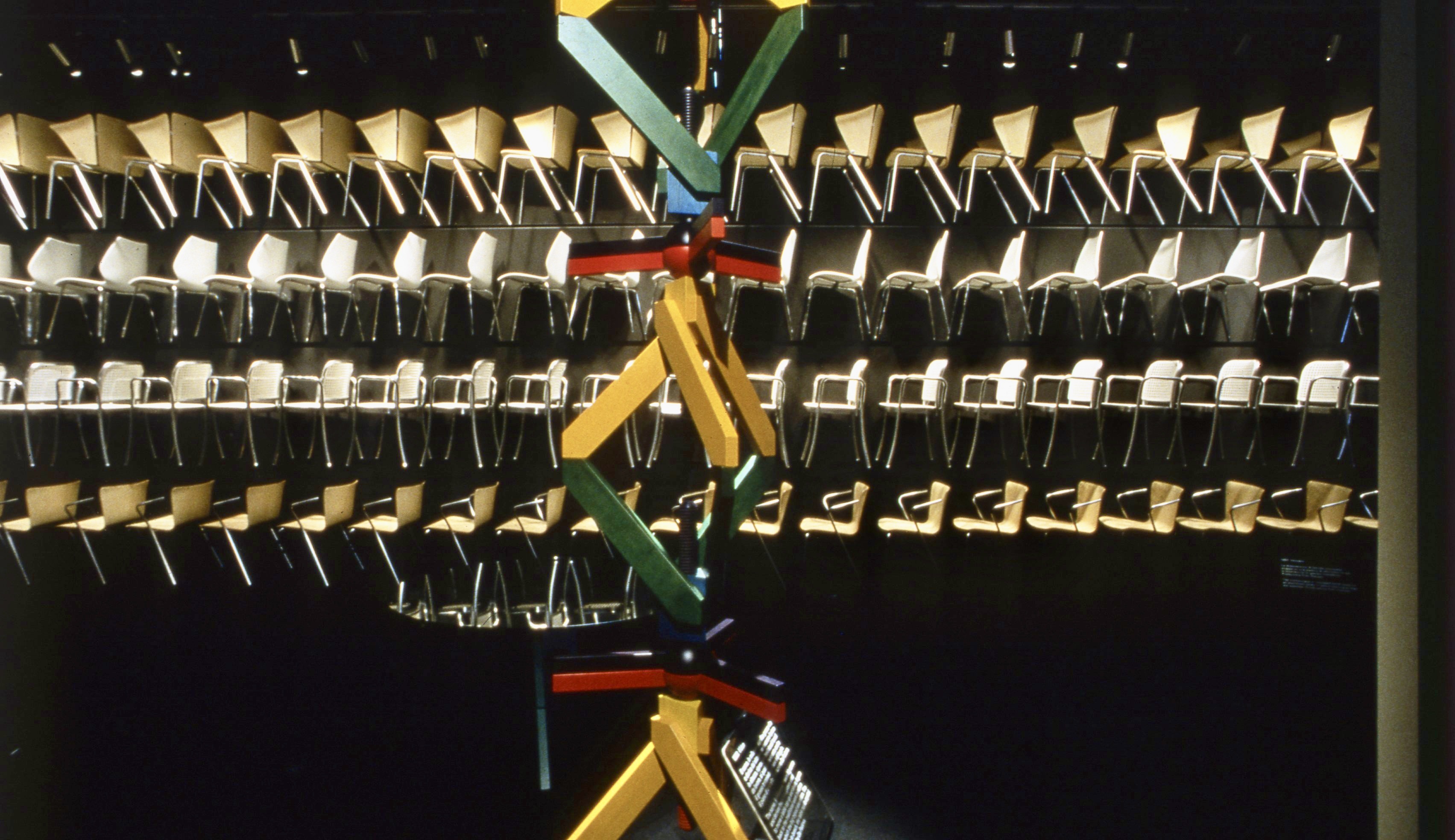

In 1997 the Milan Salone del Mobile dedicated a special exhibition to Vico Magistretti, alongside another on Gio Ponti, curated by Vanni Pasca. The installation was designed by Achille Castiglioni and Ferruccio Laviani.

2000 and onwards

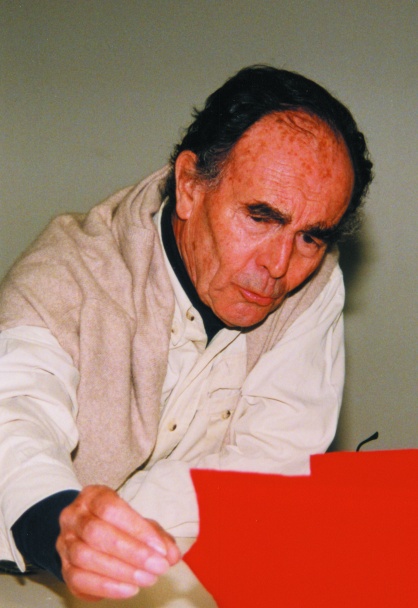

The 2000s saw Magistretti mainly engaged on his design work.

There were many new projects for Campeggi: the folding armchair Africa (2000), the Estesa armchair (2000), the Magellano (2003) and the Fan sofas (2005), the last product the architect ever designed.

There were also many products presented with De Padova: the Blossom table (2002), the chairs Cirene 03 (2003) and Basket (2004).

The last buildings he designed were a house in Saint Barth in the French Antilles (2002) and another in Épalinges, near Lausanne (2005).

In 2003 an exhibition entitled Vico Magistretti. Il design dagli anni ’50 a oggi organised by Fondazione Schiffini opened in Palazzo Ducale in Genoa.

"I wanted the objects to be seen and the set-up to be almost invisible. And I wanted the products to be seen in relation to their time, to the era in which they were designed and produced. Therefore I wanted to tell a story, grouping the products for decades, from the 1950s to the 2000s."

His design works are displayed in the MoMA permanent collection in New York, Victoria & Albert Museum in London, Museum die Neue Sammlung in Munich, and numerous other museums in America and Europe.

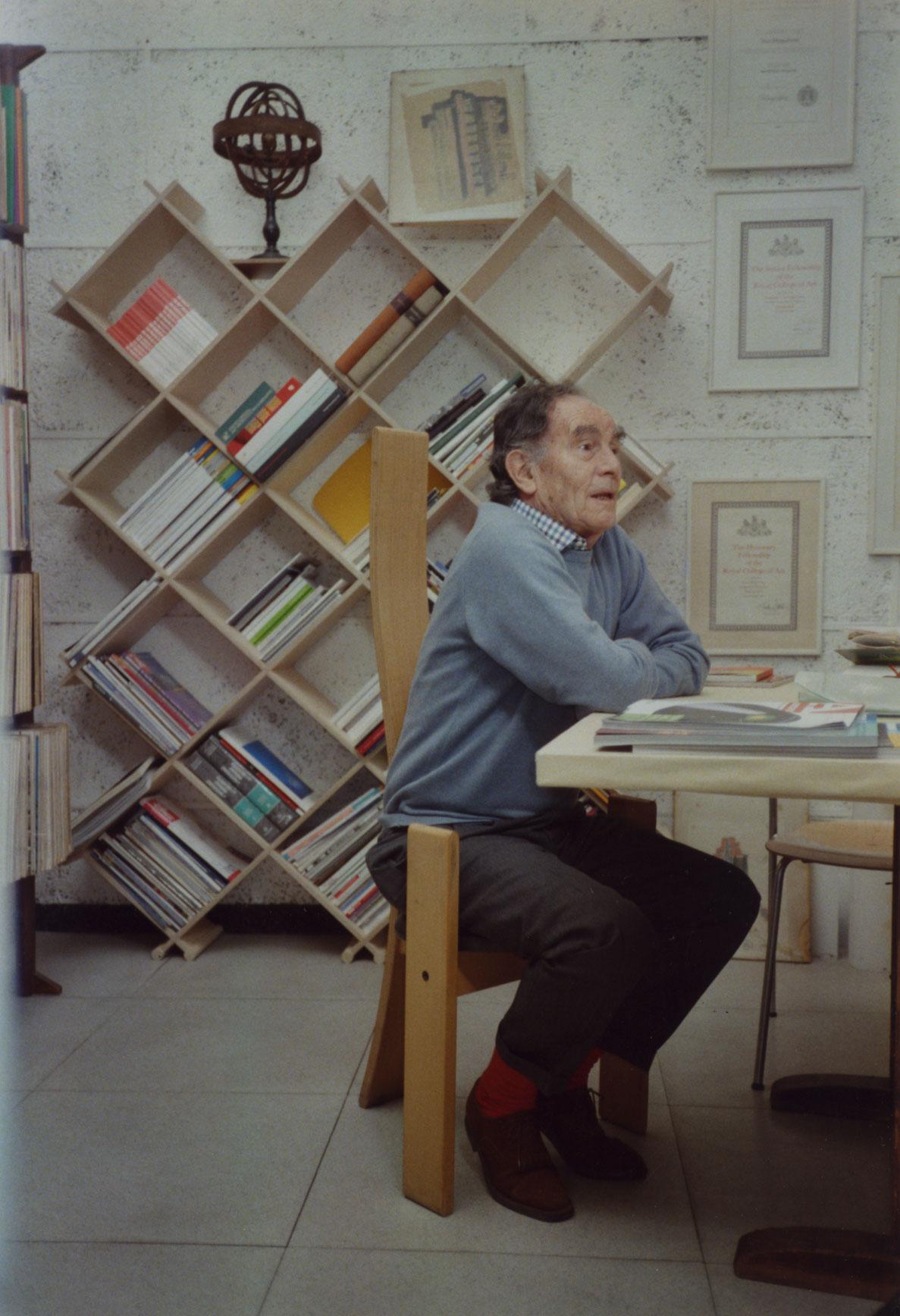

After he passed away in September 2006, his studio, where Fondazione Vico Magistretti is located, was converted into a museum devoted to the study of his work and to promoting it.